Consensus

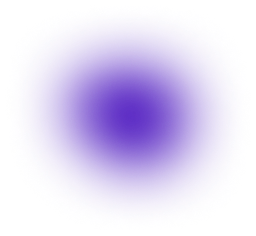

Each subnet of the IC is its own blockchain that makes progress concurrently to the other subnets: it runs its own instance of the IC core protocol stack, including consensus. Recall that the goal of consensus is to produce blocks agreed upon by the nodes of the subnet, which yields an ordered sequence of messages to be executed. This is crucial so that the upper two layers of the protocol stack – message routing and execution – receive the same inputs in every round on each node.

The IC’s consensus protocol is designed to meet the following requirements: low latency (almost instant finality); high throughput; robustness (graceful degradation of latency and throughput in the presence of node or network failures). The IC consensus protocol achieves these goals by leveraging chain-key cryptography.

The IC consensus protocol achieves these goals by leveraging chain-key cryptography. The IC consensus protocol provides cryptographically guaranteed finality. The option of choosing probabilistic finality – similar to what is done in Bitcoin-like protocols, by considering a block final once a sufficient number of blocks have built on top of it in the blockchain – is not acceptable for the IC for two reasons: (1) probabilistic finality is a very weak notion of finality and (2) probabilistic finality would increase the time to finality drastically.

The IC consensus protocol achieves all of these goals making only minimal assumptions about the communication network. In particular, it does not assume any bounds on the time it takes for protocol messages to be delivered – that is, it only assumes an asynchronous network rather than a synchronous network. Indeed, for a decentralized network that is globally distributed, synchrony is simply not a realistic assumption. While it is possible to design consensus protocols that work in a purely asynchronous setting, these protocols generally have very poor latency. In order to achieve good latency, the IC consensus protocol requires protocol messages to be delivered in a timely manner to make progress. However, the correctness of the protocol is always guaranteed, regardless of message delays, so long as less than a third of the nodes in the subnet are faulty.

The consensus protocol maintains a tree of notarized blocks (with a special origin block at the root). The protocol proceeds in rounds. In each round, at least one notarized block is added to the tree as a child of a notarized block that was added in the previous round. When things go right, there will be only one notarized block added to the tree in that round, and that block will be marked as finalized. Moreover, once a block is marked as finalized in this way, all ancestors of that block in the tree of notarized blocks are implicitly finalized. The protocol guarantees that there is always a unique chain of finalized blocks in the tree of notarized blocks. This chain of finalized blocks is the output of consensus.

At a high level, a consensus round has the following three phases:

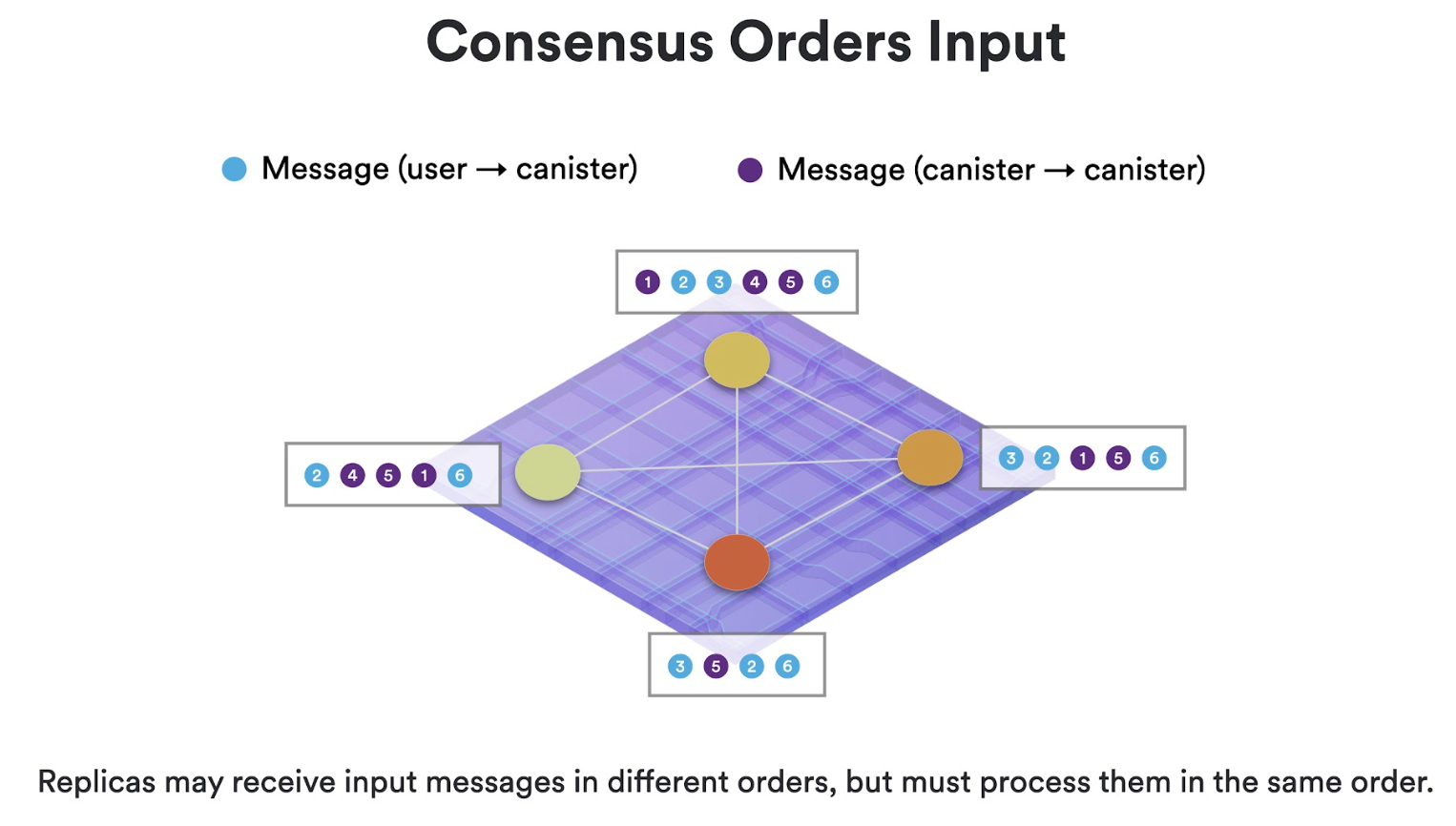

- Block making: In every round, at least one node, called a block maker, proposes a block by broadcasting it to all nodes in the subnet using P2P. As we will see, when things go right, there is only one block maker, but sometimes there may be several.

- Notarization: For a block to become notarized, at least two thirds of the nodes must validate the node and support its notarization.

- Finalization: For a block to become finalized, at least two thirds of the nodes must support its finalization. As we will see, a node will support the finalization of a block only if it did not support the notarization of any other block, and this simple rule guarantees that if a block is finalized in a given round, then there can be no other notarized block in that round.

Let us next look at the different phases of a consensus round in more detail.

Block Making

A block maker is a node that proposes a block for the current round. As explained below, a cryptographic mechanism called a random beacon is used to select one node (chosen at random) as the primary block maker (or leader) for the current round. The primary block maker assembles a block consisting of the ingress messages (submitted directly to the node or received from other nodes in the subnet via P2P) and XNet messages (sent to this subnet from other subnets). After assembling a block, the primary block maker proposes this block by broadcasting it to all nodes in the subnet using P2P.

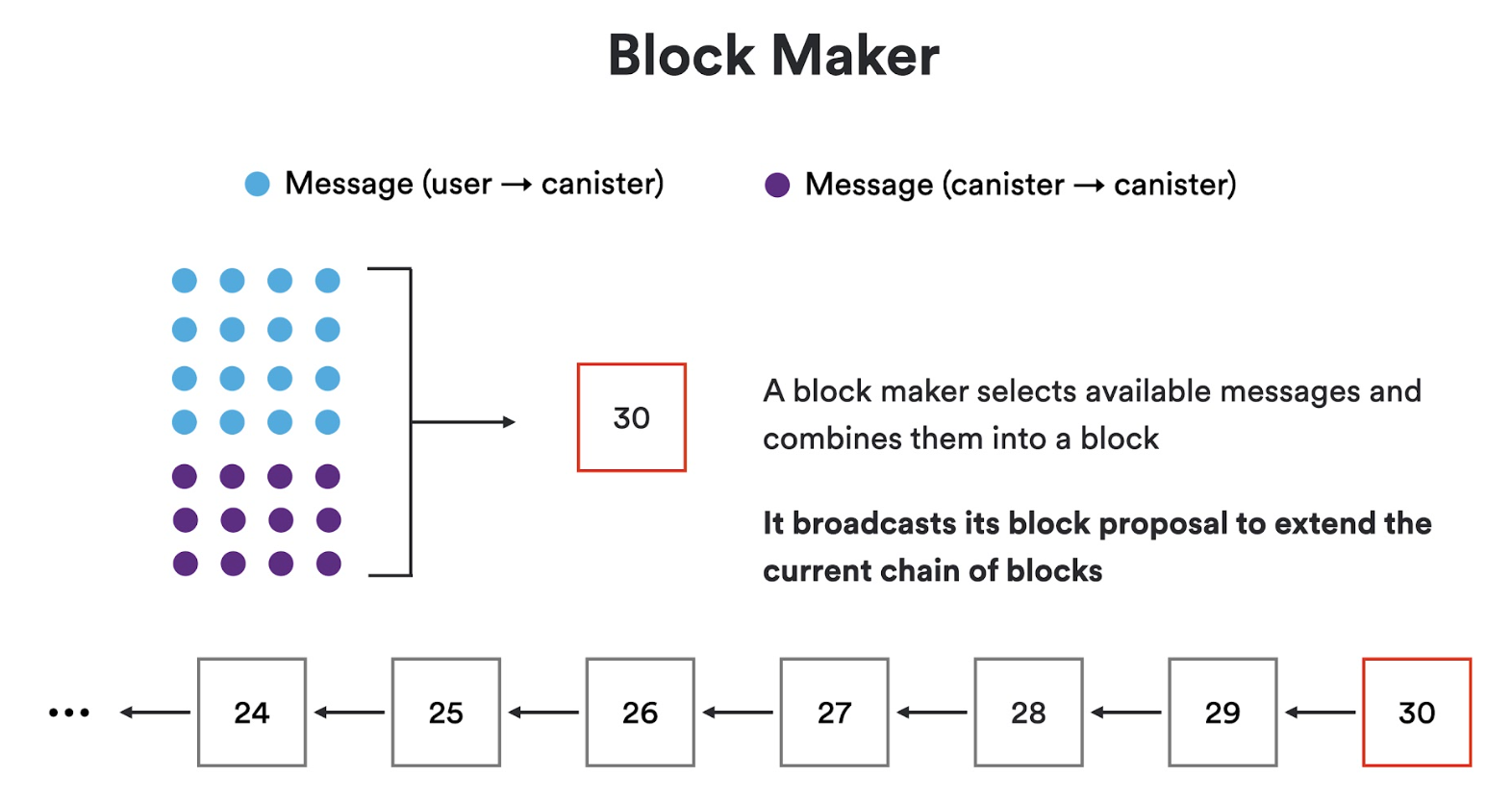

If the network is slow or the primary block maker is faulty, the block proposed by the primary block maker may not get notarized within a reasonable time. In this case, after some delay, and using the same random beacon mechanism, other block makers are chosen to step in and supplant the primary block maker. The protocol logic guarantees that one block eventually gets notarized in the current round.

The block makers for a round are chosen through a random permutation of the nodes of the subnet based on randomness derived from a random beacon. As discussed in the section on chain-key cryptography, chain-key cryptography may be used to produce unpredictable and unbiasable pseudo-random numbers. Consensus uses these pseudo-random numbers to define a pseudo-random permutation on the nodes of the subnet. This assigns a rank to each node in the subnet. The lowest-rank node in the subnet acts as the primary block maker. As time goes by without producing a notarized block, nodes of increasing rank gradually step in to supplant the (potentially faulty) nodes of lower rank as block maker.

In the scenario where the primary block maker is not faulty, and protocol messages get delivered in a timely manner, only the primary block maker will propose a block, and this block will quickly become notarized and finalized.

Notarization

When a node receives a block proposed by a block maker for the round, it validates the block for syntactic correctness. If the block passes this validity check, the node supports the notarization of the block by broadcasting a notarization share for the block to all nodes in the subnet. A notarization share is a signature share computed using the BLS multi-signature scheme. A block becomes notarized when at least two thirds of the nodes in the subnet support its notarization. In this case, the BLS multi-signature shares may be aggregated to form a compact notarization for the block.

In the case where the block proposed by the primary block maker gets notarized within a certain amount of time, a node will not support the notarization of any other block in that round. Otherwise, a node may eventually support the notarization of blocks proposed by other block makers of higher rank (but if it has already supported the notarization of a block proposed by a block maker of some rank, it will not support the notarization of blocks proposed by block makers of higher rank).

Finalization

In a given round, the logic of the protocol guarantees that a node will always obtain a notarized block (assuming less than a third of the nodes in the subnet are faulty). Once it obtains a notarized block, the node will not subsequently support the notarization of any other block. Moreover, if the node did not previously support the notarization of any other block, the node will also support the finalization of this block. It supports the finalization of this block by broadcasting a finalization share for the block to all nodes in the subnet. A finalization share is a signature share computed using the BLS multi-signature scheme. A block becomes finalized when at least two thirds of the nodes in the subnet support its finalization. In this case, the BLS multi-signature shares may be aggregated to form a compact finalization for the block.

Go Even Deeper

Achieving Consensus on the Internet Computer